New method could improve access, early detection and treatment to underserved populations

Cervical cancer is preventable through vaccination for human papillomavirus (HPV) and treatable through early detection. But the National Cancer Institute (NCI) reports more than half of all cervical cancer cases diagnosed in the United States occur in patients who have never been screened or are infrequently screened.

Barriers to screening include socioeconomic factors, a lack of awareness and a lack of access, whether patients are physically far from a clinic or do not seek care due to being uninsured or underinsured.

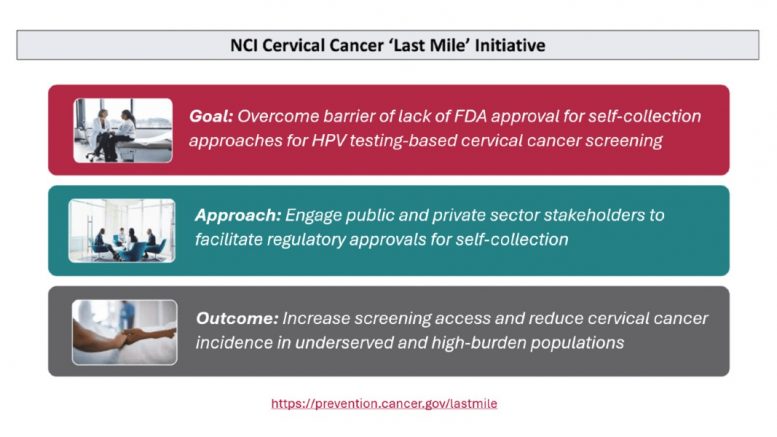

To help close the gap in access to screening, the NCI has launched the Cervical Cancer ‘Last Mile’ Initiative, a public-private partnership working to provide evidence on the effectiveness and accuracy of self-testing for HPV.

Part of this initiative is the SHIP trial (Self-collection for HPV testing to Improve Cervical Cancer Prevention). The University of Cincinnati Cancer Center is one of 25 SHIP trial sites across the country testing whether samples self-collected by patients for HPV testing are as accurate and effective as clinic-collected samples.

Leeya Pinder, MD, local principal investigator of the trial, said there are several ways to screen for cervical cancer. But primary HPV testing, rather than other methods including Pap and HPV cotesting, shows the most promise for being an effective self-testing method.

“It really gives people the opportunity to just do a vaginal swab or a cervico-vaginal swab so that they can get tested for high-risk HPV, which is usually the driver of cervical precancer and cervical cancer,” said Pinder, a Cancer Center member and associate professor in the UC College of Medicine Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Division of Gynecologic Oncology. “What we’ve been trying to do over the last several years is prove that women can actually do HPV testing on their own.”

“It really gives people the opportunity to just do a vaginal swab or a cervico-vaginal swab so that they can get tested for high-risk HPV, which is usually the driver of cervical precancer and cervical cancer,” said Pinder, a Cancer Center member and associate professor in the UC College of Medicine Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Division of Gynecologic Oncology. “What we’ve been trying to do over the last several years is prove that women can actually do HPV testing on their own.”

While other countries have approved self-collection HPV testing, the method is not currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Pinder said previous studies have shown self-testing methods are effective, especially for certain underscreened populations.

“Those populations include those who sometimes struggle with substance abuse, sometimes have a history of trauma or other kinds of abuse, those that are concerned about their immigration status or actually, many things,” she said. “These are reaching the people who for whatever reason do not have great access to a health care provider to get their cervical cancer screening.”

In the SHIP trial, patients who already have a scheduled appointment for a colposcopy, an examination of the cervix, vagina and vulva, will self-test in the clinic before providers collect samples for HPV testing and continue with their routine scheduled procedure as they normally would.

“These patients are getting two swabs, so the goal is to provide additional data that this works so that the FDA has more evidence by which to approve self-testing as a means by which we could actually target populations with limited access,” Pinder said.

In addition to self-testing potentially increasing access to cervical cancer screening, prevention and early detection and treatment, Pinder said she is excited at the potential to personalize outreach and education to individual communities’ unique population and needs.

“I think that it will provide us an opportunity to reach people by partnering with other outreach organizations such as the 513 Relief Bus, mobile mammography vans, church events,” Pinder said. “I really think it will provide us an opportunity to reach the masses.”

If self-testing is approved, Pinder noted health care providers will need to streamline communications procedures and link patients to care. This could look like follow-ups with clear next steps for those found to be HPV positive and/or at higher risk for cervical cancer and offering easy-to-access HPV vaccinations for those whose self-tests are negative.

“I think that it opens a lot of doors for us in terms of education, getting people screened and then figuring out how to link people to efficient care and provide opportunities,” she said.

Since the SHIP trial will enroll patients already scheduled to come into the clinic, community members cannot enroll themselves. However, Pinder said the Cancer Center is working to launch additional research studying HPV self-testing. This may include an early intervention program at the emergency department and comparing mail-in testing versus office testing that will provide community members an opportunity to participate in the research.