Vanessa Carter presents her rapid report at Stanford University’s MedX conference on April 23, 2017.

My journey to becoming an e-Patient activist for facial differences and antibiotic resistance started in 2004, when a car accident in South Africa left me with severe abdominal and facial injuries.

Through multiple surgeries and consultations with doctors, I became aware of the lack of online resources in health, and began working to address that. I was a marketing and design professional for 18 years, enabling me to audit the web and discover that many healthcare professionals [HCPs] didn’t have websites, which was why it was so difficult to find them.

This was partly due to medical advertising laws in the past, which restricted doctors from marketing. The truth is that being visible on the web makes it possible for patients to navigate the system and gain access to the right providers. Doctors’ websites are also a valuable channel for providing reliable patient education, and to help debunk many myths we find on the internet.

Social media is another medium being used to disseminate medical education both to patients and providers. Health Care Social Media (hcsm) promotes the professional and ethical use of the web for medicine. There are many hcsm communities in existence globally, with the first established about eight years ago by Dana Lewis in the USA.

I established hcsmSA, the South African chapter, in 2013. Members use the hashtag #hcsmSA in their tweets and we track the data on an analytics platform called Symplur. The #hcsmSA hashtag is also used for a monthly Twitter chat which focuses on various aspects of e-Health development in South Africa with a group of diverse stakeholders.

We record these chats by transcript and they are made available to the public. This is important, because this level of diverse conversation isn’t always easy or cheap to coordinate at a single event with global and local healthcare leaders contributing their perspectives in one session. This is a significant example of what Twitter chats can contribute towards research in the sector.

Challenges in expanding digital health in South Africa

South Africa is still dealing with the digital divide, that gap between people who have access to Information and Communication Technologies [ICTs] and those who do not. However, we are in the process of working towards building infrastructure that supports connectivity under the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

A recent survey found that 52 percent of South Africans were using the internet in 2016; compare that to nearly 89 percent in the United States, 91 percent in Japan, and almost 93 percent in the UK. Statistics also show that 16.1 million people use smartphones in South Africa, and that is set to grow exponentially to 21.9 million by 2021.

Patients and doctors are still learning the digital skills they need to use the tools that are available today, which is why training development is important and where the concept of simplicity comes in, whether it’s in the design of the user interface and experience or in systems that support interoperability.

HIMSS provides this excellent description of what interoperability is: “Interoperability describes the extent to which systems and devices can exchange data, and interpret that shared data. For two systems to be interoperable, they must be able to exchange data and subsequently present that data such that it can be understood by a user.”

We not only have digital literacy divides, but also health literacy issues. Much of the hard work of consolidating data from our various contact points will need to rest on our IT system. Also, our data should be able to follow us from doctor to doctor, from the public sector to private sector or from country to country.

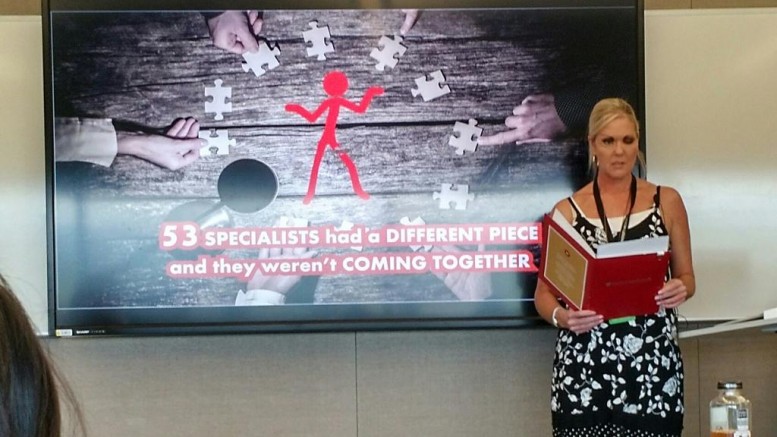

Without interoperability, there will be gaps in data sharing and room for error. In my case, I had 53 specialists who had no access to a central medical record or effective tools to collaborate. At one point, I developed MRSA. It might have been caused by overprescribing because two doctors had simultaneously prescribed antibiotics; it might also have been from my own non-adherence or from the hospital. The cause couldn’t be tracked.

Antibiotic resistance is currently one of the biggest global healthcare threats, and robust IT surveillance systems that work to collect data holistically are going to be central to managing population health. When you consider the kinds of complex information that doctors handle, and the silos that often keep them from communicating, interoperability is one real obstacle to consider when we design our IT systems.

Innovation in e-Health requires a digital thinking mindset

I think it’s important to remind people where there are still opportunities for the use of technology; that doesn’t only mean geographically, but also in certain scenarios.

For example, front-line community health workers can use tablets and other mobile devices to collect data in the field and use those devices for patient education through things like animations and videos. Training programs can also be provided to community health workers using those devices.

At the same time, the platform for all of this information sharing has to be simple for people to use; it needs to be easy to navigate for medical professionals and patients alike. That means breaking down barriers to access, whether it’s providing information in different languages, addressing illiteracy, accommodating disabilities, or acknowledging how ethnography can inform a patient’s medical decisions.

These are some of the messages that I share at events like HIMSS17, where I served as a Social Media Ambassador and talked about e-Patients in South Africa, and at Stanford University’s MedicineX, where I spoke about inclusive medical education in a rapid report called bridging medical information gaps in South Africa.

What I have gained from attending these international scholarships is the opportunity to see that much of this technology is available now. However, digital health trends like participatory medicine, big data, and co-creation won’t be easy for many healthcare providers to grasp — let alone patients.

I’ve also learned that a lot of our healthcare reform will require design thinking methodology to implement. Tim Brown, CEO of IDEO, says it well in his video about designing health and technology systems in developing countries: “Design thinking can be described as a discipline that uses the designer’s sensibility and methods to match people’s needs with what is technologically feasible and what a viable business strategy can convert into customer value and market opportunity.”

What I tell patients and doctors

I’m often asked to give advice for people who may be new to social media, and here are a few thoughts:

Don’t be intimidated by technology. Digital tools are smaller, faster, and more powerful than ever — and there are new innovations happening all the time. And they’re built for people to just pick them up and start using them.

Open yourself to the internet. Every person who joins an online conversation is adding their knowledge and experience and sharing their unique story with others. Maintaining that human contact, even over hundreds or thousands of miles, is critical. Patient communities are a growing trend with over six million already recorded on Facebook; that’s hard to ignore and they offer patients valuable support.

Share your ideas and see how they may work with existing technology. All of these digital tools started as someone’s idea, whether it was a completely new innovation or an improvement on existing technology. Think about what you need technology to do for you, and look for the tools that make that possible. And if you can’t find them? Create them.

Remember that you are part of a vast group of people with the same goals of improving health for themselves, their communities, and their nations. By knitting together a network using digital tools, people learn that they are not alone in dealing with a certain condition, doctors can find colleagues from thousands of miles away who can offer critical advice on cases, and healthcare organizations can track and address population health issues in remote rural areas where there is little structured medical care.

And finally: We’re just at the beginning of what we can achieve by working together. Ongoing developments in technology, creative new innovations, and collaboration in finding new ways for people to communicate and interact can all ensure that no one is left behind.

Topics: Big Data, Patient Engagement